|

Hemmings Motor News ⚊ Strangely enough, the oddity of this car-er, tractor-er, isn't that a tractor company tried to build a roadworthy vehicle.

The line between automobile and tractor had been hopped many times by many companies since the two industries got their start in the states in the late 19th century. Ford, most famously, marketed its Fordson tractors for many years in the early half of the 20th century, but other automobile manufacturers-Graham-Paige, GMC and Ransom Eli Olds-marketed tractors, while dozens of tractor manufacturers-Case, International Harvester and even John Deere-marketed automobiles. In fact, enough companies did so to literally fill a book, named, appropriately enough, Cars, Trucks, and Buses Made by Tractor Companies.

No, the oddest aspect of Minneapolis-Moline's 1938 Comfortractor is that, rather than jump from one distinct market to another, the company tried to blend that line between the two by placing a streamlined cab and set of fenders on an existing tractor chassis, offering both the utility of a tractor and the comfort of an automobile in one vehicle.

Though unprecedented in design, the Comfortractor represented the latest in a series of several attempts through the decades to blur-or at least make a zig-zag of-that line

Minneapolis-Moline, which formed in 1929 when Minneapolis Steel, Moline Plow (at the time known as the Moline Implement Company) and the Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company merged, began introducing original tractor designs in 1931, but by the middle of the decade was looking for a larger share of the tractor market.

Under the impression that farmers while plowing their fields-subjected to intense cold, sheets of rain, frying sun and hail that hurts like a continuous shotgun blast-would like a little shelter from the extreme elements, and that farmers could use a vehicle to handle both the duties of a tractor and of an automobile, Minneapolis-Moline began work around 1935 on a completely enclosed tractor, the UDLX (U Deluxe), that would enable farmers to plow the fields during the week, then hose the tractor off and head into town on the weekends.

"The idea was at least 20 years ahead of its time," said Jim Parrin, who undertook the majority of the restoration work on this Comfortractor for its owner, Don Wolf of Fort Wayne, Indiana. "Nowadays, you can't buy a tractor without a cab, but in the 1940s or early 1950s, there were aftermarket heat housers, which were canvas curtains with windshields. Those were very common, and putting one on your tractor was like going from a Chevy to a Cadillac."

Streamlining took off in farm tractors during the mid-1930s, and canopies, of course, had been common on tractors nearly since their beginnings, but few, if any, tractor companies at the time seemed to have thought of completely enclosing the driver. We see mention of tractors marketed from 1916-20 by Willard Lamb Velie, the grandson of John Deere, that featured a streamlined body and enclosed cab, but those sold poorly and none seem left today.

Rather than design an entirely new tractor, Minneapolis-Moline started with its Model U, which had a wheelbase of 81 inches and featured a semi-perimeter

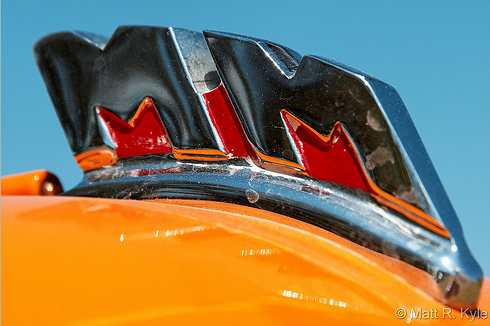

To this chassis, the engineers added the streamlined fenders and cab, which featured headlamps, a styled grille, three tip-out windshields, windshield wipers, one door in the back and a spotlamp above the door. They sunk the cab down low on the chassis, between the five-foot-tall rear tires, so low that the transmission and rear axle intruded into the cab space. Also unusual for a tractor at the time was the full, automobile-styled dash that included a speedometer, fuel gauge, oil and water temperature gauges, a cigarette lighter, glove compartment and a radio.

Minneapolis-Moline also threw in such amenities as a heater/defroster, dome lamp, a rearview mirror with an integrated clock and a foldaway jump seat so Ma could accompany Pa into town.

The axle remained the same as the Model U's, but the engine received insert bearings rather than babbitt bearings, and the transmission received some tweaking. The non-synchronized gearbox, still a five-speed with a direct-drive fifth gear, featured a special housing and second shifter that disabled the engine's first four gears at road speeds to reduce about a quarter of the rotating parts in the engine and a good deal of engine vibration, Parrin said. The shifter also bypassed the engine governor, allowing the tractor to rev higher than the normal operating redline of 1,785 rpm.

Under tractor operation, then, the UDLX had a top speed of about 24 or 25 mph, about the top range for road speeds among most tractors of the time. But when operating as an automobile, top speeds jumped to about 40 mph. Only the Graham-Bradley General Purpose tractor, which was powered by the Graham-Paige automobile's six-cylinder engine, was known to have matched those speeds.

Minneapolis-Moline introduced, amid much fanfare of its own, the UDLX Comfortractor to a crowd of about 12,000 farmers in 1938. The tractor nearly immediately flopped.

But the sales pitch fell short for other reasons too. Today, consumer research more or less dictates product development. Then, it was in its infancy, at best. Minneapolis-Moline thought they'd have a hit on their hands after employing an independent agency to research what farmers wanted in a tractor. According to an article in the October 15, 1938, issue of Implement & Tractor, more than 50 percent of the farmers who replied indicated a preference for an enclosed cab. Minneapolis-Moline's president at the time, W.C. MacFarlane, even went so far as to believe that the addition of a cab to tractors would help reverse, or at least stem, the migration of youth from the farms into the cities and the factories.

"We feel that if we can contribute to this industry machinery which takes some of the drudgery and tedium out of the farmer's round of daily toil, it will not be so difficult to persuade the younger generation to follow in the footsteps of their parents," he said at the Comfortractor's introduction.

But Minneapolis-Moline either inadequately researched their target market or plain ignored everything else they learned from those studies.

Farmers-whether due to their Puritan wool-shirt heritage or their rustic, anti-elitist nature-make the same over-the-fence observations of advice as any Madison Avenue socialite, only in reverse. To drive something that expensive and coddling would draw stark stares of disapproval from neighbors. "Farmers are very conscious of what others did," Perrin said. "Plus, the mentality was that if you got something with a cab on it, you were a sissy." The sissy comment wasn't too well-deserved. As a tractor, it performed nearly as well as the U model, which itself proved exceptional.

"It was a really good three-plow tractor, and most tractors of that day were two-plow," owner Don Wolf said. "The only place where it didn't work well was

And it took a manly man to withstand the abuses doled out by driving such an ox. Despite the low cab height compared to today's tractors, the farmer still had to climb up over the rear power take-off, which spun just inches from his leg while driving. He had to climb over the jumpseat and wedge himself in amid the back of the engine, the transmission and the rear axle. If he were any taller than five feet, he'd have found his head uncomfortably close to the ceiling, which did have a headliner-the tractor's only piece of upholstery save for the sunvisors, the seats and the rubber floor mat.

Once running, heat built up quickly inside the steel cabin. Tip-out windshields, using locking Ford window slides, provided some ventilation, but the side windows remained fixed. Many owners removed the hood to help the tractor run cooler and also removed the door to help reduce the cab's interior temperature. The enclosed cabin amplified the noises that came from transmissions as they aged.

"You were essentially encased in a reverberating drum," Perrin said.

Driving the tractor wasn't terribly easy, either. The lack of suspension would make even the tightest race-only sports car seem plush in comparison, especially at road speeds. The non-synchronized transmission required a practiced shift to change gears on the fly. Despite the height of the cab, visibility toward the front suffered. Steering, fortunately, with the short wheelbase and Ross steering gear, proved about as light and simple as an automobile.

Braking, though, separated the boys from the men, especially at road speeds. The tractor weighed 6,400 pounds-that's almost 1,200 pounds heavier than a 1975 Cadillac Fleetwood

Perrin, who runs the St. James Garage in Harlan, Indiana, said he had little problem restoring the tractor's drivetrain-he has restored many tractors, so that had become almost routine for him. The hardest part to locate was the flywheel ring gear. He searched for about a year without success and was about ready to have a new one custom cut when he mentioned the restoration to Elmer Schaefer, whose father owned a Minneapolis-Moline dealership. Schaefer, who lives about 20 miles from Perrin, had a brand-new ring gear hanging on his shop wall, perhaps the last one to exist.

However, Perrin had never worked on a tractor with this much bodywork, and this particular example came to him with a trashed cowl, dash and hood, as well as a missing front bumper and bad window glass. Perrin had new glass cut and rolled new sheetmetal panels, looking at pictures as his only reference. He finished the body in Minneapolis-Moline's Prairie Gold, the only color to deck the UDLX's flanks.

Minneapolis-Moline made about 150 Comfortractors in about May and November of 1938. As many as 10 were built as "sport roadsters"-constructed without the cab, but with the fenders, headlamps and dash-and designated UOPN. Documentation from Minneapolis-Moline is scarce-White Motor Company bought the company in 1963, and AGCO bought White Tractors in 1991-but by 1940, only about 100 had been sold; the rest went back to the Minneapolis-Moline factory in Hopkins, Minnesota, where those 50 or so tractors lost their sheet metal and were reverted to base Model U tractors. Perrin said the tractors actually performed well as rural mail carriers, for which a good number

About four or five have changed hands over the last year and a half-a fairly brisk trade for such a rare vehicle-with the latest restored example selling at auction for more than $110,000. Few exist outside of the breadbasket.

With such low production numbers and a stinging rejection, the UDLX was often panned as folly and still garners comments calling it the least successful tractor ever. True enough, there remains today a clear demarcation between automobiles and tractors, so Minneapolis-Moline seems to have failed in their effort to blend the two.

Yet, because of their rarity, you're more likely today to find Comfortractors on the field of a car show or tractor show-we spotted this one at the prestigious Glenmoor Gathering in Canton, Ohio, last year-rather than in a farmer's field. And with the wholehearted acceptance of closed-cab tractors in farming communities across the country by the mid-1970s, and with tractors nowadays featuring ever more sophisticated GPS and computer equipment, the UDLX has shown itself to be at least partially ahead of its time.

SIDEBAR:

As the story goes, the Minnesota National Guard first tested the UTX shortly before World War II at Camp Riley, Minnesota, where a guardsman dubbed it "jeep." The term spread during

He said the term actually has been applied to anything termed General Purpose as far back as 1914. A series of lawsuits, as depicted in the book, Jeep Genesis: The Rifkind Report, helped settle out both our current idea of the Jeep and who got the rights to the name.

"To summarize, nobody really knows where the term comes from," Foster said.

OWNER'S VIEW:

"But this one, we don't let too many people drive it. I'm afraid somebody would get into it and just not be able to handle it. It's unusually noisy, it's terribly hot inside, and it drives nothing like a car.

"I knew that I wanted one of these for several years, though, and I found this one up in Minnesota about seven years ago. I was surprised-the sellers had about four or five neighbors who wanted to buy it, but they sold it to me instead; that way, all the neighbors would be equally as mad at them. "But I like it because it's a very different engineering piece. It had some faults, but from an artistic design standpoint, everybody just loves it."

PRO'S:

CON'S:

Year: 1938

ENGINE

TRANSMISSION

DIFFERENTIAL

STEERING

BRAKES

CHASSIS and BODY

SUSPENSION

WHEELS & TIRES

WEIGHTS & MEASURES

CAPACITIES

PRODUCTION

PERFORMANCE

The cab provided almost as much visibility for the operator as

The cab did not interfere with the front-mounted cultivator or

In June, 2016, at the Michigan Gone Farmin' sale, described as

A on-line Aumann Auction for the Van Merchant Estate Collection

Our Research Source

|

by the constituent companies of Minneapolis-Moline. In 1918, Minneapolis Steel advertised the automobile-like style and engineering of its Twin City 16-30 tractor, which featured a fully enclosed engine and hoodsides as well as swoopy rear fenders. A year later, the same company introduced a four-cylinder engine with dual camshafts and four valves per cylinder in its Twin City 12-20-an automobile-level of sophistication compared to the primitive tractor engines of the time. Also in 1918, Moline Plow placed an electric self-starter and headlamp as standard equipment on its Universal Model D tractor.

by the constituent companies of Minneapolis-Moline. In 1918, Minneapolis Steel advertised the automobile-like style and engineering of its Twin City 16-30 tractor, which featured a fully enclosed engine and hoodsides as well as swoopy rear fenders. A year later, the same company introduced a four-cylinder engine with dual camshafts and four valves per cylinder in its Twin City 12-20-an automobile-level of sophistication compared to the primitive tractor engines of the time. Also in 1918, Moline Plow placed an electric self-starter and headlamp as standard equipment on its Universal Model D tractor.

chassis, in which the front axle and engine attached to a frame of 1-inch-by-6-inch steel plate, but the transmission and the rear axle made up the entire structure of the rear half of the tractor. Not a lick of suspension intermediated between the axles and the chassis.

chassis, in which the front axle and engine attached to a frame of 1-inch-by-6-inch steel plate, but the transmission and the rear axle made up the entire structure of the rear half of the tractor. Not a lick of suspension intermediated between the axles and the chassis.

Farmers, still struggling with the Depression and well-known for their thrifty hardiness, balked at the $1,900 price tag. At the time, the Model U and comparable John Deeres cost about $1,000. A 1938 Ford Deluxe Tudor sedan, by comparison, sold new for $725. Theoretically, a farmer could have bought the UDLX and wouldn't have needed to purchase a car. In fact, according to Perrin, Minneapolis-Moline salesmen were instructed to park their family cars for a month and drive the UDLX instead.

Farmers, still struggling with the Depression and well-known for their thrifty hardiness, balked at the $1,900 price tag. At the time, the Model U and comparable John Deeres cost about $1,000. A 1938 Ford Deluxe Tudor sedan, by comparison, sold new for $725. Theoretically, a farmer could have bought the UDLX and wouldn't have needed to purchase a car. In fact, according to Perrin, Minneapolis-Moline salesmen were instructed to park their family cars for a month and drive the UDLX instead.

in tight corners-you'd bang up those front fenders because they stuck out further than you'd expect them."

in tight corners-you'd bang up those front fenders because they stuck out further than you'd expect them."

Brougham-and had drum brakes on the rear wheels only. Granted, the drums were 16 inches in diameter, but "it just doesn't stop very good even if it's in tip-top shape," Perrin told us.

Brougham-and had drum brakes on the rear wheels only. Granted, the drums were 16 inches in diameter, but "it just doesn't stop very good even if it's in tip-top shape," Perrin told us.

were put into service in Minnesota. Of the 150 Comfortractors, nearly 80 are accounted for today (2005) and maybe 25 of those are in restored or roadworthy condition.

were put into service in Minnesota. Of the 150 Comfortractors, nearly 80 are accounted for today (2005) and maybe 25 of those are in restored or roadworthy condition.

the war and afterward, as Minneapolis-Moline produced the UTX for the U.S. Air Force and Army Corps of Engineers. Minneapolis-Moline eventually made attempts to claim the term, but according to Jeep (you know, the Willys Jeep, with a capital J) historian Pat Foster, "Army soldiers called lots of things jeeps-planes, trucks, tractors-just because they had the G.P. initials on it."

the war and afterward, as Minneapolis-Moline produced the UTX for the U.S. Air Force and Army Corps of Engineers. Minneapolis-Moline eventually made attempts to claim the term, but according to Jeep (you know, the Willys Jeep, with a capital J) historian Pat Foster, "Army soldiers called lots of things jeeps-planes, trucks, tractors-just because they had the G.P. initials on it."