|

When James Oliver was born to his parents, George Oliver, a shepherd, and his wife, Elizabeth Irving, August 28, 1823, in the tiny village of Newcastleton, Scotland, it may have been hard to

imagine that this child of humble beginnings would become one of America's most influential inventors and industrialists. Or that James would one day have a son, Joseph D. Oliver, who would also become a business guru and

build a mansion in South Bend, Indiana, called Copshaholm.

George and Elizabeth Oliver had nine children in 21 years. James, the last child, was born when Elizabeth was 42. Six years later when her brother was widowed, Elizabeth undertook raising his four children who ranged in age from infancy to six years old.

The Olivers, extremely religious, were Presbyterians. James learned to read and write in a church school. Cholera struck Scotland in 1832, bringing business to a virtual halt. George and Elizabeth were hard pressed to make ends meets. In addition, George, who had been injured in 1833 while driving sheep to England, was unable to walk without a cane.

In 1830, John Oliver, one of their older sons, restless and penniless, tied up all of his belongings in a red handkerchief and left for America, working his passage as a seaman. He found work at a dollar a day and wrote his family in Scotland in glowing terms.

John described his new home in America, telling about a country where firewood was plentiful and in fact, were sometimes in the way. He also wrote about eating meat three times a week. (Actually he ate meat daily, but was afraid his family wouldn't believe that.) He also explained that he ate at his employer's table-unheard of in Scotland. Lured by John's letters, another of the Olivers' son, Andrew, and a daughter, Jane, immigrated in 1834.

The Oliver family left their village in March 1835, their few remaining belongings piled on carts. Neighbors accompanied them the first two miles on their journey to Annon, Scotland, a waterfront town near the border of England. The trip to New York took seven weeks and four days, with severe weather causing a rough crossing of the Atlantic.

Upon arriving in New York, the family continued to Geneva, New York, to the farm of James Goodwin, father-in-law of John Oliver, the first of the Oliver sons to leave Scotland. The Olivers made the seven-mile trip to John's small log-framed farmhouse in two days.

For the first time, the Olivers had plenty to eat-meat at every meal, potatoes, onions, and a food the Olivers had not seen before: corn on the cob. James, thinking the corn on the ear was a new way of cooking beans, cleaned off the cob and asked that the "stick" be refilled.

The long journey had taken its toll on the Olivers' pool of money and by this time, it was nearly all spent. With finances a major concern, James began working as a chore boy at a nearby farm for 50 cents a week and board.

Using a neck yoke, James carried lunch to field workers, chopped wood and did other menial tasks for his employer. His employer liked his energetic ways, and when James finally had to leave, his boss offered to triple his wages if he'd return.

That autumn, James moved with his family to Alloway, New York, a small town settled by Scottish immigrants. Here they resided on a farm until the next summer. Prompted by the wish to obtain inexpensive land available in the Midwest, the Oliver's moved from Alloway to LaGrange County, Indiana in 1836. The trip, by boat and wagon, took 21 days.

Meanwhile, their daughter Jane, who had left Scotland in 1834, had married Charles Roy, who owned 60 acres in Clear Spring Township, LaGrange County. Son Andrew, who also left in 1834, had obtained 160 acres of virgin land from the government. James and others in the family set about to help him clear this land.

In December 1836, several of the Oliver children, including James, moved to Mishawaka, Indiana, probably prompted because of better opportunities available there. The St. Joseph Iron Company, was attempting to build a dam across the St. Joseph River. James worked there for $6 a month until the spring of 1837, when a depression left the company without ready cash.

James attended George Merrifield School for a brief time, quitting to help support his mother after the death of his father on September 6, 1837. Attempts to help his mother led to many jobs and adventures.

James cut and sold wood, did menial chores, labored as a farm hand, and, at one time, worked for Alexis Coquillard, a South Bend pioneer who was attempting to dig a canal to link the Kankakee and St. Joseph Rivers. Sleeping in a shanty while wolves howled nearby proved too much for him. James became ill with a type of malaria and quit.

James and his brother Andrew then found work in a small foundry owned by the South Bend Blast Furnace Company of Mishawaka. There James learned to scratch castings and cast molds, but the company failed in 1840.

Later he worked in the gristmill, packing flour into wooden barrels for $15 a month. The Lee brothers found him highly industrious and asked him to take up the trade of a cooper in the shop where the barrels were made. Here he gained considerable knowledge as a carpenter.

Joseph Doty, a direct descendant of the Mayflower pioneers, worked with James. After the death of his wife, Joseph moved to Mishawaka with his daughter, Susan Catherine. James, 20, inclined to be bashful, became enamored of Susan Catherine, 19.

Although she rebuffed him several times, he persevered and won her hand the following year. James traveled by raft down the St. Joseph River to South Bend where he obtained the wedding license, and James and Susan Catherine were married May 30, 1844.

James and Susan began married life in a slab cabin on the banks of the St. Joseph River near Alger's Island in Mishawaka. They purchased the cabin for $18 and paid $7 annually for the land on which it stood. While James improved the cabin (the best lumber cost $6 per 1,000 board feet), Susan wove rag carpets on a borrowed loom.

They lived in the cabin eight months, which James later described as "the happiest days of our lives," and then sold it for $50. The transaction, which gave them a little cash, brought them a house and three-fourths of an acre of land on the north side of the river.

James had to work for considerably less than $15 a

James and his wife Susan soon needed more room in the new home they had purchased in Mishawaka. A daughter, Josephine, had been born April 6, 1846, and a son, Joseph Doty, called "J.D.," had arrived August 2, 1850. They resided in this home until 1858 when they moved to South Bend.

After William Gillen's furnace failed financially in 1847, James went to work for the St. Joseph Iron Company that made plows as well as castings. Here James seized an opportunity to better himself financially. Among the castings produced were 22-pound flanged plates used beneath railroad joints for strength.

The company was unable to meet production schedules because of the inability of molders to cast the plates according to specifications. James contracted with the company to produce 100 tons of the plates for $5 "and five shillings" a ton.

He completed the contract and produced 35 tons more in four months. He made $675. James later admitted he almost killed himself doing it, but this contract and the earlier purchase of a lot in Mishawaka for $75, where he built a house.

The St. Joseph Iron Company also manufactured cast iron plows, as did almost every foundry and blacksmith in the country. For James, plow production provided a link between the foundry, which he loved, and the land, for which he harbored an attachment stemming from boyhood in Scotland.

However, James became apprehensive about his future when the St. Joseph Iron Company changed hands and he decided to investigate the possibility of buying into a small business. While waiting for a late train in Goshen, Indiana, a major plow manufacturing center, he inadvertently heard that a small foundry on the west race in South Bend, owned by Ira Fox and Emsley Lamb, might be for sale.

By May 5, 1855, James Oliver and a molder co-worker, Harvey Little, each purchased one-fourth interest in this building. Cast iron plows were one item this little foundry produced.

Six weeks after the purchase of the foundry, it was devastated by rampaging waters of the St. Joseph River. James referred to this in later life as his "first great discouragement."

Oliver and Little managed to survive and the plant went back into operation in November of 1855. Oliver and Little then purchased Lamb's half interest and renamed it "South Bend Iron Company." That name appeared on the title page of their first book of accounts.

February 6, 1857 high water again damaged the plant, but Oliver and Little were undaunted and the plant soon was back in production. They bought scrap iron for one and a quarter cents a pound and converted it to almost anything that could be made of cast iron at a charge of five cents a pound.

They made iron window weights, caps and sills for windows, kettles, spiders (frying pans with legs and long handles), pulleys, stove castings and grates. They also produced bob shoes (metal strips that fit on sled runners) for the fledgling Studebaker Brothers Company.

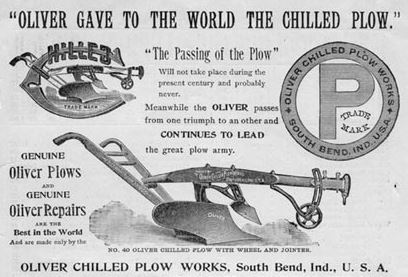

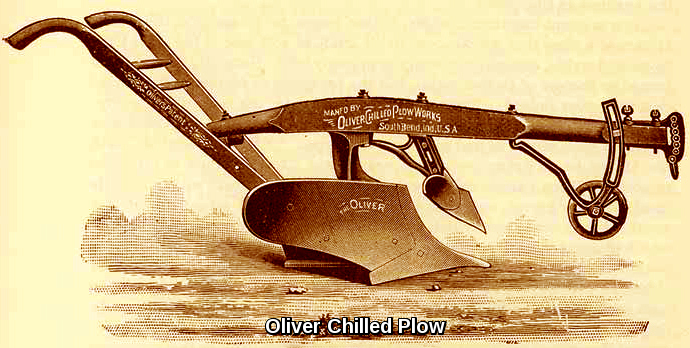

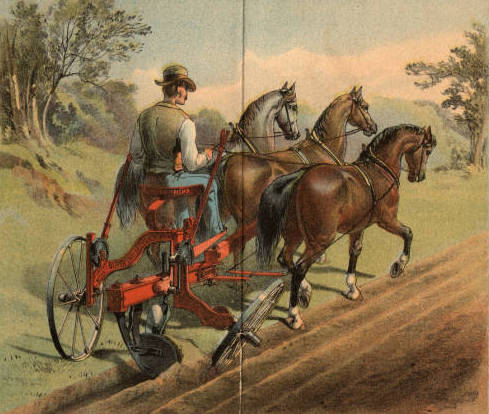

James, molder, designer, salesman and bookkeeper for the company, also continued experimenting with ways to produce a better plow. All plows of that era were "walking plows." Pulled by two horses (or other beasts of burden), the farmer walked behind and guided it through the soil with two handles. Cast iron and steel plows both wore out rapidly. Dirt stuck to the moldboard and made it difficult for the animals to pull. This forced the plow from the ground with a jerk, endangering the plowman. The dirt had to be scraped from the moldboard with a paddle every few minutes.

June 30, 1857, James obtained his first patent from the U.S. government, entitled

To get nearer to the plant, the Oliver family moved in 1858 from Mishawaka to an old brown frame house purchased for $600, on unpaved Main Street near downtown South Bend. In 1868 the house was moved to the back of the lot and a larger structure of brick was erected.

So successful were Oliver and Little that they were able to advertise a reward of $500 to anyone who could, "chill or harden plowshares with equal success without infringing on their patent."

The firm was renamed "Oliver, Little & Co." in 1860 when Thelus Bissell, a machinist, was taken into the partnership. Each now owned a third interest in the firm. But on Christmas Eve, 1860, disaster struck again. Fire destroyed their plant on the West Race with an estimated loss of $4,000, a fortune in that era. They carried no insurance. James Oliver later branded this event his "second great discouragement."

By March 1861, Oliver, Little & Co., had succeeded in erecting a building on the West Race where operations were resumed. That year they produced, in addition to plows, six "fluted columns" weighing 4,902 pounds for Saint Mary's college, two "iron columns" for Schuyler Colfax, "brackets and vestibule cornice" for the city jail and "sewer crates," also for the city.

Window weights, more than four tons of columns, cornices and stairs were produced for a contractor. The plows sold for $6.50 each. Business was improving and more buildings were acquired on both sides of the race.

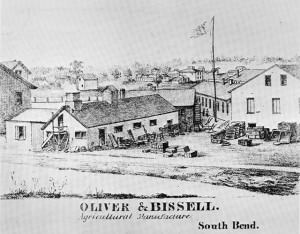

In 1863 Harvey Little retired from the firm. Thelus Martin Bissell acquired half interest in the company, now renamed "Oliver and Bissell," and James Oliver acquired the rest. That summer about 20 men were on the payroll, and demand for the plows was such that the price was increased to $7.50 and the business continued to expand.

Oliver and Bissell realized they needed more capital. George Milburn, a wealthy wagon manufacturer in Mishawaka, purchased a third interest in the company, with Oliver and Bissell retaining one third each. The company was, once again, renamed "Oliver, Bissell & Company" and the work force increased to 25. Wages ranged from $1 to $3.50 per day.

Approximately 1,000 plows were produced and sold in 1864. Of these, 100 were the patented steel share plows that sold for

The Civil War was in progress and prices continued to rise as demands for production increased. The company also made 70 iron columns for the Main Building at Notre Dame, after a disastrous fire consumed the old one. These columns hold up the Golden Dome structure on the University of Notre Dame's Main Building.

From this period of the Oliver company history the expansion was phenomenal. By mid-1865 the staff again had been increased to plant capacity and all on the payroll were working overtime. Meanwhile, Joseph (J.D.) Oliver, James' son, was getting in on the company's ground floor.

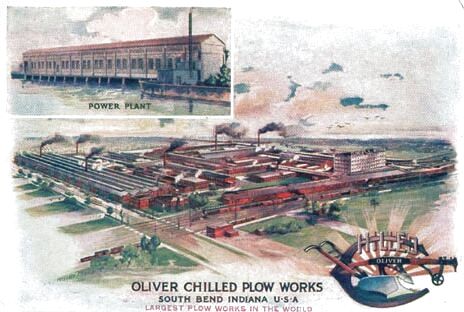

The Olivers purchased 32 acres of the "Perkins Farm," on the southwest edge of South Bend, for $30,000 and construction of a new South Bend Iron Works plant on that site started almost immediately.

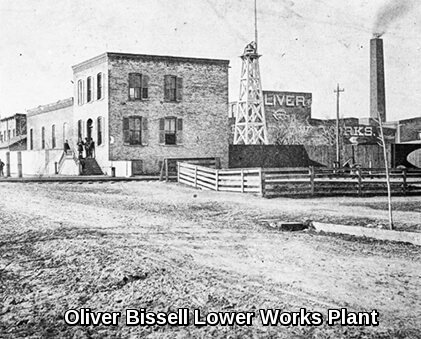

Full production continued at the "Lower Works," as the old factory on the West Race was known, while warehouses were built, railroad tracks laid, and water and sewer lines extended to the new "Upper Works."

The new complex had five buildings with a total area of 200,000 sq. ft. Plans called for employment of 400 men who would

Plow sales in 1878 reached 62,779. A total of 30 to 40 railroad cars loaded with 5,000 to 7,000 plows left the new "Upper Works" at a time, for shipment from coast to coast.

In November 1878, Brownfield, who had been president for almost nine years after the resignation of George Milburn, tendered his resignation, and in January 1879, James Oliver was elected president. Prior to that, James had held the title of superintendent.

Meanwhile, "branch houses" were being established across the land to handle distribution of the plows. The size of the Oliver company simply overwhelmed its opponents, including the South Bend Chilled Plow Company, which had been organized by Bissell and allegedly used Oliver patents in an attempt to capitalize on the reputation of the Oliver firm, still known as the South Bend Iron Works.

The year 1880 was one of great expansion. A record was set in production and sales of plows, new buildings were erected, riding plows were being produced on a large scale, the manufacture of malleable castings was started, and more rail tracks were laid to the Oliver property.

On May 4, 1881, James purchased the Chess and Vincent properties in the 300 block of West Washington Street. The Chess mansion was an imposing structure. Though it was only 19 years old, James sold the interior woodwork and hired a New York architect who had designed Canada's parliament buildings to enlarge and re-design the house.

To increase the grounds, James sold and moved the Vincent house next door and hired an army of workmen to lay stone. The new 60' x 102' house (not to be confused with Copshaholm, which was built in 1896 by J.D. Oliver, James' son) had three stories, a slate roof, 10 bedrooms with dressing rooms, bathrooms with closets attached, and a billiard room.

James Oliver and his family moved into the new home at 325 W. Washington Street on December 10, 1882, and on January 17, 1883, held a reception for 500 guests who danced in the third floor ballroom and dined on food prepared by a Chicago chef.

James had come a long way from the simple life of a shepherd in Scotland, but in spite of affluence, he remained a simple

This was to be his last residence. "James' wife died in the home in 1902, and he died there on March 2, 1908 at age 84." The house stood vacant until 1911, when South Bend School City (now South Bend Community School Corporation) purchased and razed it. South Bend Central High School was erected on the site.

At the time of his father's death, J.D. Oliver was 58 years of age and had begun working in the foundry full time from the age of 16. He had been a director of the factory since he was 20 years old, so the transition from father to son was easily accomplished.

Joseph Oliver (J. D.) was a financial genius and it is doubtful James would have done so well without J.D.'s financial guidance. While James was frugal, J.D. realized money often was earned by spending some of it. Because of J.D.'s modesty, it was not generally known that James almost always left details of financial management to his son.

At a meeting after the death of his father, J.D. was elected President, Treasurer and General Manager; James Oliver II (J.D.'s son) was named Vice President and Joseph Ford (J.D.'s brother-in-law) was named Secretary.

These three were also the directors of the company started by James Oliver. Thus J.D. held almost the entire issue of Oliver company stock; had been named executor of his father's will; and he was responsible for the plant and more than 2,000 employees.

Annual production at the time was very high. In 1909, J.D. launched plant expansion to double the size of the plant's footprint and developed plans to expand sales into Russia and build a factory in Canada. The Oliver Opera House block was remodeled and the Oliver Hotel annex, now seven stories tall, was opened a few months later.

In 1911, plant operations started in the new plant the Oliver's had built in Hamilton, Ontario. J.D. correctly perceived vast amounts of Canada's Northwest wilderness would be opened to agriculture, and the plant was part of a plan to get part of that business.

On May 1, the first carload of plows was shipped from Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and by summer's end, 30,000 plows

J.D. had contracted with International Harvester Company to handle distribution and sales for the Oliver Canadian plant. This satisfactory arrangement for both companies continued until 1919 when the Oliver's sold the Hamilton plant to International Harvester.

Farming in the United States was steadily becoming mechanized, and the Oliver's greeted it fully. A new era had been opened in 1905 when a gasoline engine was mounted on a traction truck to pull several plows.

Gasoline farm tractors and gang plows (a large plank that has several plow blades fastened to it) developed rapidly, and on September 30, 1911 a "world's record" was set when an Oliver 50-bottom (50 blades) gang plow, pulled by three LaPorte, Indiana-built Rumley Oil-Pull tractors, turned 50, 14-inch furrows at one time, a width of almost 60 feet!

That same year three International Harvester tractors pulling a 55-bottom Oliver gang plow set another record by plowing an acre in less than four minutes, a far cry from the days when a farmer walked eight and one-fourth miles behind a team of horses and plow to turn an acre.

When World War I broke out in 1914, J.D. prepared for troubled times. "We shall not attempt to profit by present conditions," he wrote. After the U.S. entered the war in 1917, J.D. was called to Washington to confer with the nation's food administrator, Herbert Hoover.

But the war not only had to be supplied with arms and food, it also had to be financed. J.D. and Frank Hering, an Oliver Vice-Director, criss crossed Indiana setting up fund-raising and bond-selling committees in every community.

J.D. organized 22,000 schoolteachers to sell thrift stamps for bond purchases through school children to their parents. He often brought down the house when he spoke of "the fires of hell licking their lips in joyful anticipation of the advent of Kaiser Wilhelm" (the German war leader).

In addition, to ease the food shortage for employees in South Bend, J.D. established a community garden. Fifty acres near the plant were divided into 50 by 100 foot patches. The families of 301 workers participated in the project. J.D. awarded $50 in gold for the best crop return.

When the 1920s arrived, business indicators looked good, but disaster was ahead. Farm prices began to drop. Farmers were unable to pay debts and stopped buying agricultural implements. The company held the largest stock of manufactured goods and the largest stock of raw materials in its history, all purchased at high wartime prices.

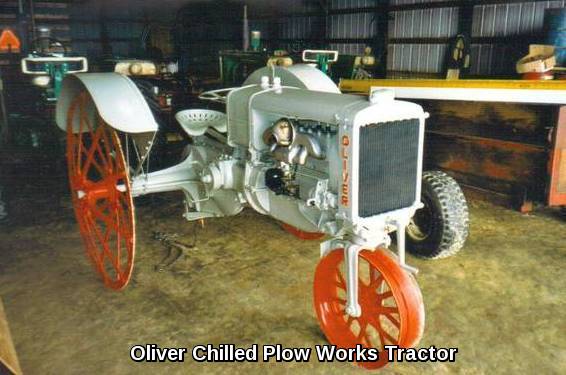

Around this time (mid-late 20's), the Oliver Chilled Plow Works lost a lucrative contract with Henry Ford's Fordson tractor,

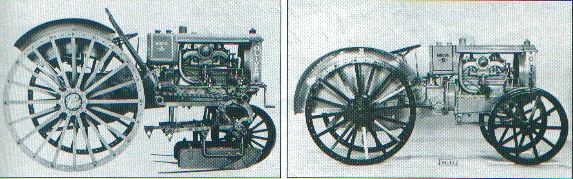

The Plow Works needed to make up the revenue loss

from Ford so it started to experiment with the creation of a tractor of their own. The tractor they produced was called the "Oliver Chilled Plow Tractor." There were only about 20 manufactured and distributed throughout the U.S., where it was well received. Only one is known to exit today. The Oliver Chilled Plow Tractor had its demise in 1929 with the company's merger into the Oliver Farm Equipment Company.

Because of its strong financial condition, the

Oliver Chilled Plow Works weathered the crisis. J.D., however, did not fare so well in spite of the appointment of the operating committee. In October 1923, he fell victim to a four-month illness, described as "tired break-down," from which he never fully recovered.

J. D. resigned many of the outside directorships he held and gave up the presidency of the Purdue University Board of Trustees, on which he had served for 18 years. He returned to his "Oliver Chilled Plow Works" office February 11, 1924, where he remained active until the business was sold.

In 1923, increased competition from other full-line farm implement companies forced the Oliver Chilled Plow Works to choose between an enormous expansion with a program to include more implements, such as, tractors or joining together with manufacturers of different types of farm tools and establishing its own full-line company.

J.D. Oliver elected to join other manufacturers. At a special meeting of stockholders on February 1, 1929, he was authorized to organize a new company, to be known as the "Oliver Farm Equipment Company," and take over the Oliver Chilled Plow Works and the Hart-Parr Company of Charles City, Iowa, a company which manufactured tractors.

J.D. also purchased the Nichols and Shepard Company of Battle Creek, Michigan, which made threshing machines, corn pickers and combines. Soon after this merger, American Seeding Machine

Company of Springfield,

The "Oliver Chilled Plow Works," as such, ceased

to exist on March 30, 1929. The executive office posts of the new "Oliver Farm Equipment Company" were divided among three of the merging companies,

with J.D. as Chairman of the Board, a post he held until resigning on December 13, 1932.

J.D. Oliver died on August 6, 1933, in Copshaholm, (name is from the birthplace of his grandfather in Scotland) the home that he had moved into with his wife, Anna Gertrude, and their young family in 1897. He was 83 years old.

Notice the tractor pipe frame under the tractor on the left. It appears

|

month until the Spring of 1845, when he went to work in a blast furnace owned by William Gillen. There, James learned the molder's trade. In 1852, James and Susan sold their house, purchasing a larger home along with ten acres of orchard on the south side of the river.

month until the Spring of 1845, when he went to work in a blast furnace owned by William Gillen. There, James learned the molder's trade. In 1852, James and Susan sold their house, purchasing a larger home along with ten acres of orchard on the south side of the river.

James was 32 years old, South Bend's population was less than 2,000, but the company, the town and James were destined to grow together despite considerable adversity.

James was 32 years old, South Bend's population was less than 2,000, but the company, the town and James were destined to grow together despite considerable adversity.

"Improvement in Chilling Plow Shares." It covered a new way to process a plow point, or share, to an extremely hard surface. This was his first improvement in the plow. Many were to follow and the Oliver Plow became "the most popular plow in the world."

"Improvement in Chilling Plow Shares." It covered a new way to process a plow point, or share, to an extremely hard surface. This was his first improvement in the plow. Many were to follow and the Oliver Plow became "the most popular plow in the world."

$17.50 each. They also made hundreds of "double shovels" and some 25-road scrapers for which they received $8 each. Castings were sold for 10 cents a pound.

$17.50 each. They also made hundreds of "double shovels" and some 25-road scrapers for which they received $8 each. Castings were sold for 10 cents a pound.

cast 50 tons of metal into 300 plows daily. A new 600-horsepower Harris Steam Engine powered the machinery. On January 17, 1876, the engine was started and the new plant went into operation.

cast 50 tons of metal into 300 plows daily. A new 600-horsepower Harris Steam Engine powered the machinery. On January 17, 1876, the engine was started and the new plant went into operation.

man with simple tastes, who preferred the heat of his foundry and the dirt of a farm to the elegant surroundings of his new home.

man with simple tastes, who preferred the heat of his foundry and the dirt of a farm to the elegant surroundings of his new home.

had been shipped. Among buildings constructed in Hamilton that year were two large docks to provide for two lake carriers to be used for shipping Oliver products.

had been shipped. Among buildings constructed in Hamilton that year were two large docks to provide for two lake carriers to be used for shipping Oliver products.

which Oliver was supplying many parts for, because Henry built a Fordson plant in Ireland and began moving everything over there.

which Oliver was supplying many parts for, because Henry built a Fordson plant in Ireland and began moving everything over there.

Ohio and the McKenzie Potato Machinery Company of LaCrosse, Wisconsin, were acquired.

Ohio and the McKenzie Potato Machinery Company of LaCrosse, Wisconsin, were acquired.